Harnessing fintech for a big leap in financial inclusion - lessons from East African success

Fintech has been pivotal making strides in financial inclusion in East Africa, the cradle of mobile money. These technologies have made financial services affordable and convenient.

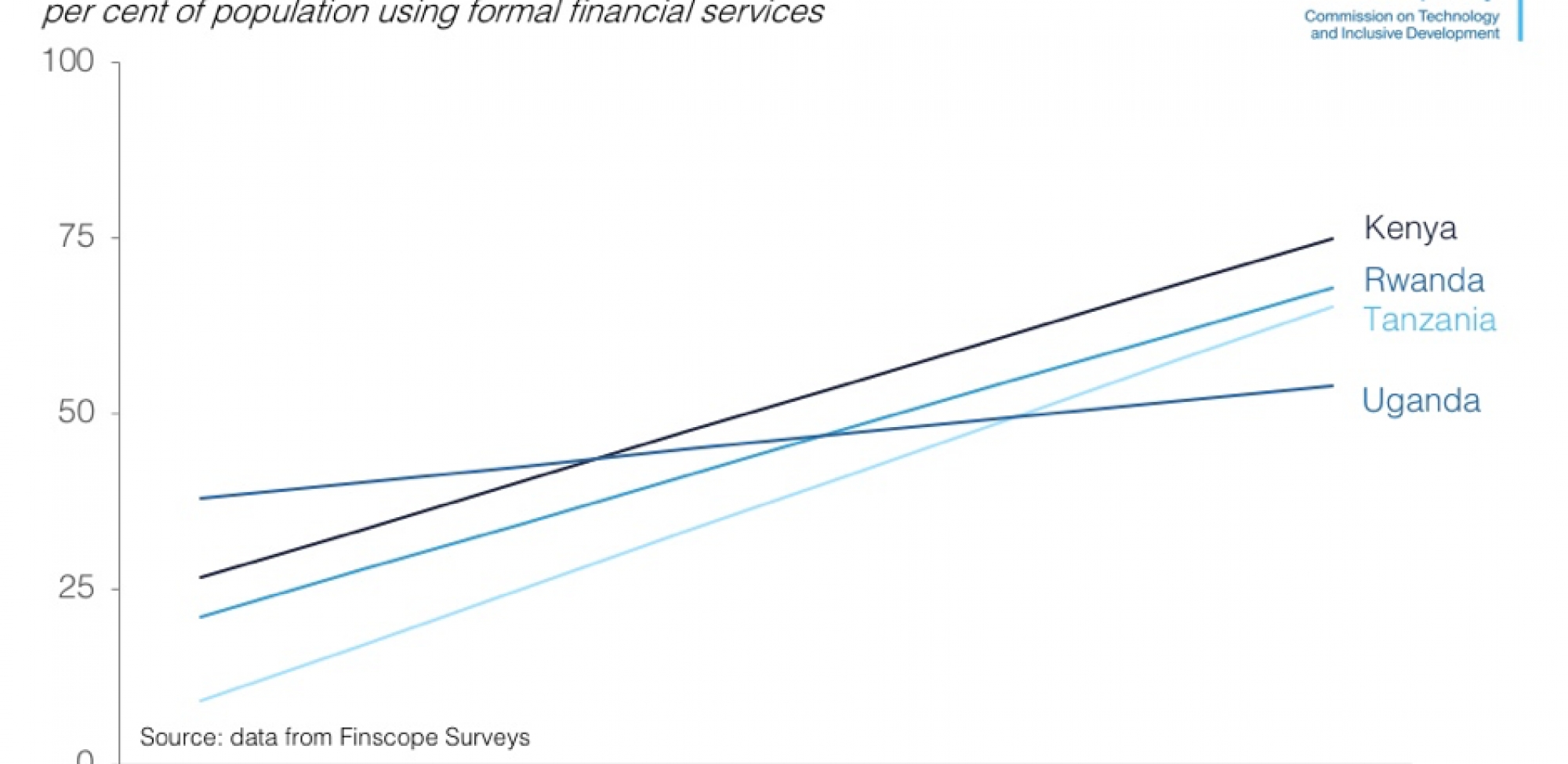

In just a decade, utilisation of formal financial services has grown dramatically in East Africa:

These are remarkable achievements that point to a rapid catch-up in this dimension of development.

The Pathways for Prosperity commission, in its first event to engage stakeholders, sought to learn what is behind this success; to what extent did fintech contribute; what challenges remain; and what are the next steps in consolidating these achievements? Key lessons from the event:

The greatest barrier to providing financial services to unbanked populations in developing countries is the cost of bringing brick-and-mortar banks to sparsely populated areas. In many developing countries, financial institutions are concentrated in urban centres and people living in rural areas have to travel great distances to access them – a trip they often cannot afford. The operating costs of fintech are much lower, allowing for cheap and profitable delivery of financial services. Mobile money agents are ubiquitous and require little investment to offer cash-in-cash-out services. The barriers for enrolment of users are low – usually just a cell phone and registered SIM. Mobile money has enhanced the convenience of financial services and allowed for quick peer-to-peer payments with significantly lower fees for the services. The cost of transfers ranges between 1 and 3 cents per dollar transacted, way below 10% charged for such transfers through the traditional banking systems, making it the most cost-effective way to send and receive money.

Central banks in East Africa implemented forward-thinking strategies to enable the success of digital financial services. They adopted a test-and-learn approach to regulation of fintech start-ups: allowing pilots of fintech products into the market to test them, assessing risks and then applying regulations. This agile and responsive approach gave new services the room to take root and grow. Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Rwanda also instituted national financial inclusion councils comprised of regulators, operators (both mobile network operators (MNOs) and banks), business interests and policymakers, who together shaped the priorities for financial inclusion. These platforms allowed for constructive engagement between these parties and swift resolution of conflict and tension.

When mobile money was first introduced, banks worried about unfair competition, as MNOs are not subject to strict financial regulation that inhibit banks. Over time this perception changed and banks appreciated that MNOs provided complementary services. They allowed banks to reach customers cheaply through dense agent networks. Some banks even got involved with mobile money by becoming the agents where users could get cash out. Other banks partnered with MNOs on mobile credit and mobile insurance products. For example, the network operator Safaricom partnered with the CBA bank in Kenya to launch M-Shwari; Vodacom partnered with CBA in Tanzania to offer M-Pawa, and MTN partnered with CBA in Uganda to launch MoKash. These are complete banking products which allow clients to save money with earning interests, or to borrow unsecured loans.

In addition to bank-MNO tensions, there was also friction among MNOs. The first was around the exclusivity of agents. In the early days of mobile money, MNOs would insist that agents only serve customers on their own mobile network, limiting the ability of other providers to build a comprehensive network. Furthermore, first-movers resisted the push to link their systems with others operators (“interoperability”) because they had made substantial investments. This meant customers could not send money across accounts with other MNOs, thereby reducing network benefits and stunting financial inclusion. Both these tensions were resolved as the advantages of overall business growth and the sharp decrease in the cost to users outweighed the fears of losing market share.

While regulation in East Africa has been forward-thinking, regulators are still slow to respond to new products. Fintech developers constantly push the frontier, but regulators are not keeping pace. Capacity constraints – a lack of expertise and resources to make risk assessments – are the most cited cause for delays. One other solution may be for regulators to set up standardised testing environments for new products, in much the same way that health regulators have standard requirements for new food or medical products. This would mean the complex task of risk assessment could be at least partly automated. New products would be tested in a controlled virtual environment, without exposing customers to risk. An automated checklist of minimum requirements and stress tests would prevent lengthy delays where analysts pore over new apps.

Another factor that slows regulation is the lack of coordination between regulators (primarily communications and financial regulators). Entrepreneurs have to liaise with multiple regulators in order to get products to market, and there can be a mutual stalemate pending a decision by the other regulator. To avoid such regulatory gridlocks, coordination platforms, such as the national councils for financial inclusion in these countries, can be used.

Fintech has allowed for greater access to financial services, but utilisation continues to lag behind access. Market operators have to provide products beyond mobile money, but new products, such as mobile credit and insurance, remain under-developed, and utilisation of mobile money for retail purchases has not benefited the poorest.

The absence of digital identification (e-KYC), low financial literacy, and credit risks are some bottlenecks to utilisation. In order to improve utilisation, regulators and market operators have to push for cost-effective universal identification, leveraging digitisation as an enabling tool. This has to be coupled with financial education efforts and the creation of user-friendly credit and insurance products for consumers with low financial literacy. For instance, credit providers could devise better repayment regimes that are more intuitive for customers, and insurance providers could offer products that hedge against weather-related risks in smallholder agriculture.

We also have to be wary of existential risks to the system: without a successful fintech ecosystem, it is difficult to grow utilisation for the poor. Cybercrime presents the biggest risk to confidence in the fintech sector. Unsurprisingly, cyber security is now high on the agenda of regulators and providers, and is key to consumer protection. Sustained growth in the utilisation of fintech products will require enhanced capacity to prevent such crime, and the ability to deal with it quickly and fairly when security breaches occur. There is room for regulators and adjudicators to step up into this space.

Judging credit worthiness is a major constraint to providing credit to the poor and micro-enterprises, who rarely have collateral to borrow against. The risks associated with provision of unsecured credit can be mitigated with credit scores based on behavioural attributes of the borrowers. L-Pesa in Tanzania uses a customer’s repayment track record to evaluate credit-worthiness, while Tala Mobile uses phone data, mainly based on data on routine habits. Disrupting the high cost of credit screening and security is pivotal for growing lending to the underserved. Using big data analytics as an alternative to traditional credit scoring systems and secured lending will enhance operations of microfinance institutions, which rely heavily on these scores.

Additionally, as fintech start-ups and banks move to provide mobile credit products, the credit reporting bureau’s (CRB) role should change in response. Mobile credit lenders have higher interest rates than traditional banks on small loans, which could lead to higher chance of default and a negative report at the CRB, thereby adversely impacting their eligibility for credit in the future. Moving forward, CRBs may consider a nuanced approach to credit scoring by encouraging both positive and negative credit reports, or allowing reports to exist on a spectrum, creating a more complete view of debtors. This could be coupled with customer education on mobile credit products, as well as using behavioural insights to encourage repayment. The mitigation of mobile credit risk is critical to the success of fintech products generally. If people are excluded from mobile credit because of crude risk scoring, we may see them abandon financial products altogether.

The ultimate aim of financial inclusion is to engender inclusive economic growth, so the focus of fintech needs to move beyond access to impact. Researchers from MIT and Georgetown have looked at the impact of M-Pesa on poverty in Kenya, and their results show that over a period of six years mobile money has lifted 186,000 families out of poverty, with female households reporting greater impact. More research of this sort needs to be done to assess the effect of fintech products on poverty, particularly via savings and credit products offered to families and small-to-medium-sized enterprises. These research efforts will help bolster efforts to ensure utilisation, and will inform decision makers in developing countries of the pitfalls and best practices for new financial technology for development.