Pathways for Prosperity Commission. (2019). Positive disruption: health and education in the digital age. Oxford, UK: Pathways for Prosperity Commission.

Positive disruption: health and education in a digital age offers guidance on how digital technologies can be used to improve the lives of people in developing countries, while keeping a careful eye on the limitations and risks of focusing solely on hardware over people and processes. Technology is not a silver bullet and history is littered with poor investments in this area. To ensure health and education services are effective, efficient and equitable, governments need to be wise with their choices. The time for these strategic decisions is now; waiting will risk further lost opportunities and lives further entrenched in inequality. This report sets out realistic visions for how developing countries can significantly improve their health and education systems by making effective use of data-driven technology, and more importantly, what governments working with stakeholders need to do next.

Positive disruption sets out a vision for how developing countries can significantly improve health and education systems by making effective use of data-driven technology. It examines potential benefits of digital technologies, and offers guidance on how to achieve change.

Technology, if properly harnessed, can be a game changer for health and education, for everyone; it can revolutionise patient health and the way students learn.

If digital technology reached the poorest and most marginalised people in the world effectively, vast human potential could be increased. Solutions are not just about shiny technology – but rather about diagnosing and fixing systemic problems first and using technology appropriately.

Digital solutions embedded in health and education systems can improve service delivery: by improving productivity and interconnectivity, and enabling more effective organisational designs. Getting this right presents vast opportunities, but when governments get it wrong, this will result in lost potential.

We offer five future visions that could soon be a reality for health and education in developing countries – if the right investments are made now.

Not taking action not only results in missed opportunities, but also risks further entrenching existing inequalities. This report offers a way forwards and highlights key digital building blocks to lay the digital foundations for future generations now.

The challenge

Delivering health and education services in developing countries is notoriously complex, and this report does not shy away from the many failures of technology. But with this dose of realism, we maintain that digitally enabled technology has the potential to create more effective, efficient and equitable health and education systems by looking beyond the clinic and the classroom, to transform the underlying decision-making, management and administrative apparatus.

This report describes the necessary digital building blocks to realise this vision, and provides a set of principles to help make digital technology a positive disruptor, rather than just a distraction to policymakers.

Vast human potential is being lost to inefficient health and education services. In a digital age, there is a risk that not taking action now could further entrench existing inequalities. 250 million school-aged children are out of school, and 330 million are in school but not learning. While access remains an issue, lack of quality services means that people are not gaining the education or healthcare that truly benefits them and enables them to thrive – both now and in the future.

Huge sums are spent on health and education worldwide to improve human capital, and more careful investment could enable great savings. This report focuses on how learning and healthcare services can be more effective; how such services can achieve their goals more efficiently; and how such services can boost equity in access and outcomes, targeting those typically left behind.

Children in less-developed regions spend less time in school and learn less per school year

People across the developing world live longer, healthier lives than they once did, and benefit from more education than even a few decades ago, but they still remain behind those who live in richer nations. On average, the learning outcomes – in terms of learning-adjusted years of schooling – for children in sub-Saharan Africa are just under a third of those of children in North America.

There is considerable variability between countries in terms of how efficiently they use resources for health and education. For instance, in countries where children receive around 8 years of schooling, learning outcomes vary from 4.3 learning-adjusted years (Angola) to 6 learning-adjusted years (Gabon).

The unevenness of this performance suggests this is not simply an issue of financing. For example, Madagascar, Bangladesh and South Africa all have similar child mortality rates, but South Africa spends 19 times more than Madagascar and 13 times more than Bangladesh on healthcare. These differences in efficiency also tend to translate into large equity gaps.

Resources are often used ineffectively, suggesting serious failings in health and education systems and the broader structures within which they are embedded. Serious issues of exclusion remain; the poor, marginalised groups, and women are all too often left behind.

Source: World Bank (2019d), Gapminder (2019), Pathways Commission analysis.

Note: This figure uses data from 2013. Expenditure is adjusted for purchasing power parity, and is reported as 2011 international dollars. The size of a circle represents a country’s population.

Technology can make systems more efficient, but silver bullets rarely deliver without a clear understanding of the broader operating environment. Technology alone is not a cure; it can be a vital part of efforts to improve outcomes, but it must be deployed alongside a genuine desire to understand and solve broader system constraints. There needs to be an emphasis on health and education systems – looking beyond the classroom and the clinic – and how technology can improve them.

The opportunity

Digital interventions, embedded in health and education systems, can improve service delivery in three ways – boosting productivity at the point of delivery, improving interconnectivity within the health or education system, and allowing for more effective organisational designs.

If scaled up, appropriate digital technologies could provide cost-effective quality services, which will have positive impact on future generations, creating healthier and better-educated populations, allowing developing countries to harness their great human potential. Innovative digital technologies that are well-connected to their contextual environments have already led to progress in health and education services.

Positive Disruption highlights a number of evidence-based examples from around the world where technology has been used effectively by NGOs, tech entrepreneurs and governments working together in partnership to improve the quality of services, with demonstrable impact both in learning and health.

The Mobile Vital Records System (VRS), a mobile web-based application helped raise the birth registrations from 28% to 70%, helping authorities to track and improve individuals’ health. Recording births is a key aspect of health planning: without this data, countries only have approximations of the size, health, and longevity of populations. Mobile VRS has essentially become the main system for recording births in Uganda. At $0.03 per registration, the cost is very low, and Mobile VRS is likely to become an integrated part of the forthcoming national ID system.

Kenya has seen huge success with a national literacy program led by the Ministry of Education. Many school children here perform at learning levels more than two years lower than their grade would suggest. A national literacy programme called Tusome, which uses digitised teaching materials and a tablet-enabled teacher feedback system, is boosting children's abilities; students’ learning performance has increased by more than a quarter. If it were to be scaled up, it could close the learning gap for children.

Personalised adaptive learning digital tools are beginning to show their potential to bridge gender differences in students’ attainment: onebillion’s “onecourse”, which delivers content and practice on a tablet, was found to prevent a gender gap in reading and mathematics skills from surfacing among first-grade students in Malawi – potentially by overcoming sociocultural factors responsible for gaps emerging in traditional classroom settings.

Adaptive learning software that tailors learning based on data collected on a child’s performance is also showing huge promise. An example of this is MindSpark in India, which achieved an increase in maths performance of 38% in five months, with estimated costs as low as $2 per pupil, per year, if scaled up to over 1000 schools. The technology empowers pupils, tailoring lessons to their strengths and working on their weaknesses. (See video below.)

A community health workers’ program run by Muso sends staff to identify and treat patients in their homes in the most remote areas. This program has helped the country to achieve the lowest child mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa (reducing child mortality tenfold). Technology in the form of simple mobile devices and a data dashboard has helped amplify successes. The opportunity for better monitoring and staff management, together with actionable data in the hands of field staff, has meant that the same health workers increased the number of households they were able to visit by 10% a month, thus also improving their productivity. (See video below.)

While technology offers much promise, this will not be guaranteed without deliberate action. Several factors exacerbate the issues that many women and girls face in accessing technology. As previously highlighted in our Digital Lives report, there is a significant gender gap in access to mobile technology. The gap was seen across seven countries, irrespective of age, education, location and income level. And even when there is equal access to technology, some technologies may exhibit inherent biases that disadvantage women.

The emerging lesson is that technology can help bridge gaps in both access to and outcomes in healthcare and education, but the foundations of any technological solutions need to be set in place with careful consideration of gender from the outset.

Access to education is increasing, but quality is not. Millions of children are in school but not learning. In India on average a child might attend school for 10.2 years but only receive 5.8 years of learning, technology like Mindspark can make a big difference by improving the quality of available education.

In some areas of Mali, Muso's community health workers are providing proactive healthcare, where the healthworker goes out to see patients at home. This has transformed child-mortality rates to the lowest in sub-Saharan Africa, now using digital technology they are amplifying their success.

Five near-future visions for health and education in developing countries in a digital age

In the near-future, digital technologies will enable countries to completely reimagine the delivery of health and education services. Positive Disruption highlights five visions of how technology-driven tools and the data underpinning them can improve the delivery of health and education services in the future. Governments can achieve these future visions if they get their investments right and make holistically designed strategic choices that solve problems first and use appropriate, effective and sustainable technology.

Careful and deliberate low-cost data collection will make it possible for health and education systems, supported by digital technologies and artificial intelligence or machine learning, to continuously learn and improve by creating feedback loops for decision-making at every level.

The systems of the future have the potential to be proactive, inclusive systems, targeting the citizens most in need of services. Education and health services can be provided for those who are not reached by conventional methods, drawing technological resources not just to those who can afford them, but to those who need them most.

Learning and healthcare will be personalised in ways that can be tailored to the individual needs of all, even the poorest and those left furthest behind.

Automation and new formats of service delivery will redefine but not diminish the roles of teachers and healthcare staff.

Improving communication technologies (from phones to video-link, and perhaps virtual reality) creates the opportunity for a virtual system, bringing down the walls of classrooms and clinics and providing expertise even to remote areas.

What next?

The time is ripe to plan for scale, and to bring digital technologies into health and education systems. Decisions made by funders and policymakers today will determine whether the roll-out of digital technologies will exacerbate failings and inequalities already present, or instead be a force for positive disruption, leading to more effective, efficient and equitable systems.

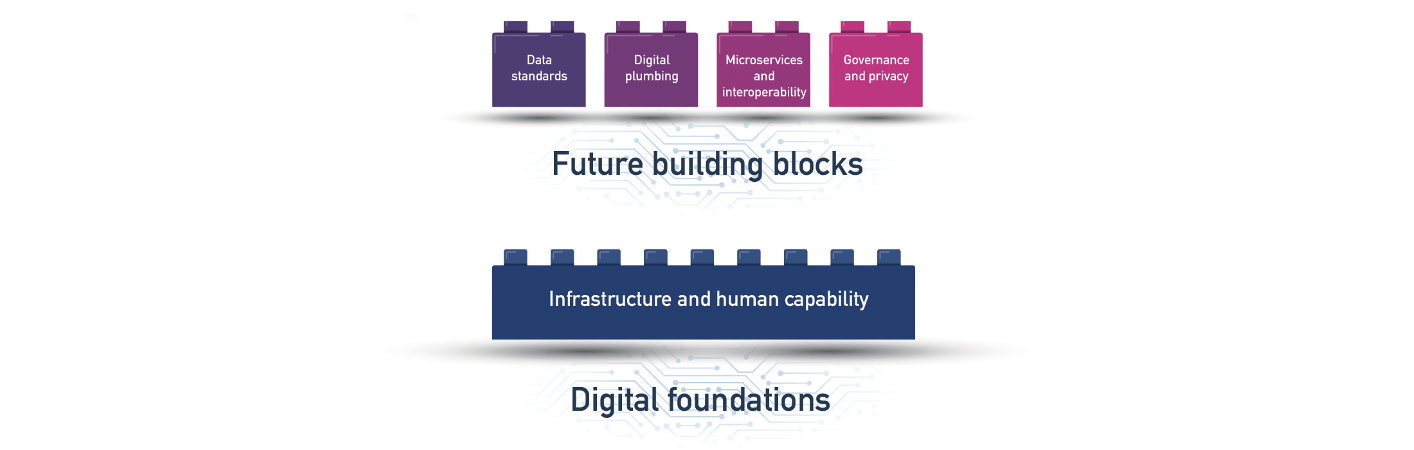

For implementation at scale, the focus will need to be on promoting innovation in the private and public sectors, ensuring that progress is inclusive, and creating the right digital foundations. The key driver for success in using digital technologies in service delivery – the effective use of data – requires a focus on creating the right enabling digital foundations and digital building blocks.

Governments must create space for innovation in service delivery, both in the public sector and with private actors. Access, affordability and digital literacy must all be given special attention to ensure education and health services are inclusive. Data will be the fuel that powers future digital systems. The five future visions put forward in this report all rely on data to reimagine the design and architecture of these systems.

However, not all countries enter the digital age on an equal footing. Before digital technologies are implemented, countries must ensure that the right digital foundations are in place: digital infrastructure, such as access to electricity and internet, and digital skills. Inclusive access needs to be embedded upfront, and not be an afterthought.

Clear rules around data governance and privacy must be established: these future visions require significant centralisation of data about citizens, and while the potential upside is great, so too is the potential for harm.

How to do it?

Positive disruption offers four principles for everyone – citizens, workers, policymakers, funders and entrepreneurs – to be able to harness the opportunities of the digital age for better health and education, and to avoid the potential pitfalls.

Deploy technology only when it offers an appropriate and cost-effective solution to an actual problem.

Focus on the content, data sharing, and system-wide connections enabled by digital technology, not exclusively on hardware.

Invest in digital building blocks, not just the bulk collection of raw data, in order to move towards the systems of the future.

Ensure that the technology genuinely works for all by making deliberate efforts to engage with and build solutions for people who are typically left behind.

Good healthcare and education are critical for women, girls, men and boys to thrive. In the digital age, education is essential to ensure communities are not left behind and they can adapt to the future landscape of work, while good healthcare ensures longer lives and stronger communities.

Decisions made today by funders and policymakers will determine whether digital technologies can truly change education and health service delivery in developing countries.

Policymakers should critically monitor progress in terms of scale, impact and cost. If done carefully and judiciously, positive disruption is possible, and developing countries will move closer towards better health and education for all.

Footnote: We have become aware that a line in this report could be misinterpreted. We have therefore corrected page 57 of the report to better reflect that the Aadhaar ID card in India is voluntary.

Read our two new policy briefs:

Managing health in the digital age and Managing education in the digital age

If you work for the government, business or civil society and are interested in improving the quality of health and education delivery, have a look at our two new policy briefs: Managing health in the digital age and Managing education in a digital age.

These two briefs set out a number of practical considerations for countries wanting to embrace digital technology to improve health and education for everyone. Better outcomes for students and patients are of course not inevitable – particularly when the focus is often on procuring shiny new hardware or deploying technology for technology’s sake. The ability to use data to improve the management of these complex systems offers real, practical, opportunities to policymakers, as we explore in these briefs.