Silicon government

Ezra Klein, founder of Vox.com and American journalist, recently compared the Washington D.C political circuit and the Silicon Valley technology bubble: "D.C…. is shaped by people watching solvable problems prove impossible to solve. Silicon Valley is shaped by people watching impossible problems prove possible to solve."

To marry the contrasting worlds of policy and technology might seem paradoxical. Can you tackle public policy challenges that affect citizens’ lives using technology’s fast-paced innovative methods, in an environment more used to being guided by deep analysis and the complexities of a wider political economy?

At the Young Civil Servants Policy Hackathon, held by the Pathways Commission in Johannesburg, 30 young professionals who work in government and social sectors from across Southern Africa gathered to explore what it was like to do so. In one day, they were introduced to human-centred design methods, tools frequently used in Silicon Valley, to frame problems around human needs proposed by these professionals themselves. These problems included:

-

Digitizing access to legal aid in Namibia;

-

Minimizing illegal substance abuse among youth in South Africa;

-

Tracking hospital and health centre performance for better decision-making in Lesotho.

Of course, no one expected to solve these problems in a day. After all, many brilliant minds and experts have been tackling these issues, in some cases for years. While applying our fresh perspectives to generate novel solutions was one objective, the event’s primary goal was to provide a framework and method that the young civil servants could use in their respective organizations.

Why ‘hack’ public service challenges with human-centred design?

In theory, governments and social sectors already have adequate tools to deliver human-centred policies and services; they already use political representation and engagement, as well as more formal polls, surveys and focus group discussions.

While centering services around the end-user might sound obvious, it is less practiced than expected. Why should a policy maker be concerned about the mental and capacity overload for a clinical nurse, when policy makers need nurses to gather much needed information and data to demonstrate results, for example? Recognizing that not thinking about the end-user is commonplace, how might public service delivery be re-centred on the end-user, instead of the broad policy outcomes? And how can this thinking solve problems and deliver impact?

So, what is human-centred design?

Human-centred design tools can provide policy makers with a more direct and engaged way to surface user needs in wicked social problems. Policy makers may know that 10% of substance abuse victims are under the age of 15, but human-centred design can help them understand the social, emotional and structural reasons behind their behavior, and reduce ingrained assumptions. Instead of conducting a year-long study to understand behaviour and conducting an expensive pilot, human-centred design creates tighter iterative loops between research and design, in order to continually discover and refine solutions.

Some core tenets of the human-centred design process, popularized by global design firm IDEO and Stanford’s d.school, include:

-

Focus on human values: genuinely putting oneself in your users’ shoes;

-

Talk less, do more: building and making things happen to think and learn;

-

Radical collaboration: bringing unlikely collaborators together.

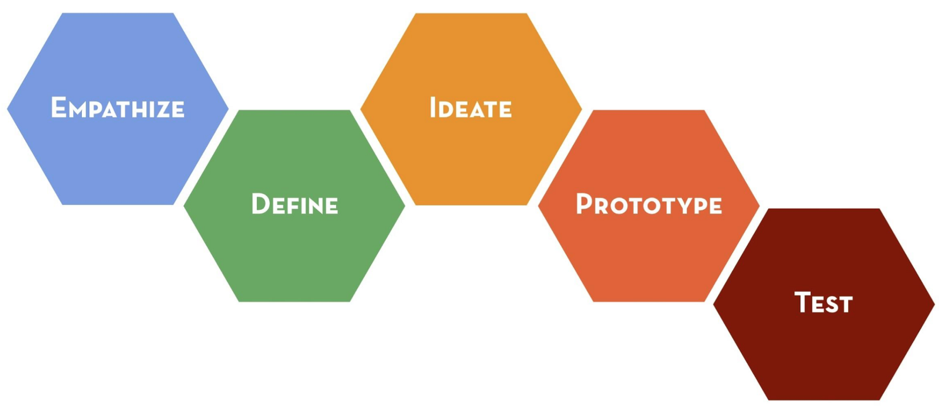

Many of these principles have been codified in a design thinking process that draws inspiration from disciplines like ethnography, human-computer interaction, and industrial design. While there is no fixed design process, the following 5 steps capture the main activities in any design process.

During the Commission’s policy hackathon, we absorbed these principles and applied them to the real life problems participants brought as case studies, resulting in intriguing technology-based solutions, and some applicable takeaways.

What did we take away from the day?

Think micro, not just macro.

For policy makers, well-versed in the conversations around macro trends and systems thinking, it is easy to analyse issues logically, and from a high level. How might we remove bottlenecks in the collection and distribution of health data? How does one’s socioeconomic ability affect the efficacy of the legal aid process? While having a big-picture context is helpful, such language and framing results in little new perspective.

The hackathon participants were able to speak directly to key stakeholders of the problems involved at the frontline or micro level to better understand their perspectives. These stakeholders included a nurse at a substance abuse clinic in Johannesburg, and researchers at the Clinton Health Access Initiative in Lesotho. In practice, policy makers running such a process would have spoken to end users themselves too, like substance users or people applying for legal aid, to ensure their ground perspectives were understood.

Even so, zooming into issues down to the micro-level helped reframe the problem significantly. For example, having spoken to the nurse, the problems facing substance abuse clinics were reframed around her. They were struck by her generous spirit, and how many administrative tasks ended up taking away precious time she had with her patients. To alleviate her workload, the team devised a system that triaged patients’ needs, so that the nurse would be able to spend her time most efficiently with the patients that needed her help the most. By zooming in more closely on a key stakeholder, the solution they proposed had the potential to improve the experience for the end user, the patient.

Emotions are more important than you think.

Considering a solution and its emotional resonance can determine the solution’s success in unexpected ways. Thinking about delighting the user is not a new phenomenon in the private sector (particularly in tech), but is not a primary consideration in many public sector solutions. Sometimes, things simply have to work. They don’t have to make people happy. Thinking about how emotions can support a policy or nudge people into action is an important part of sustaining a solution.

Yet, emotions can be a powerful lever when designing for sticky solutions. A good example of this is IDEO’s work in increasing the uptake of HIV prevention products among women in South Africa. These drugs had already proven to be highly effective in fighting HIV, but why were women not taking them? From speaking to women they realised that the packaging was stigmatising its use and even had the potential to lead to domestic violence from partners. Framing HIV products as medicine was a no-go, because male partners become suspicious.

The team’s solution was to re-package the drug with a fresh brand, much like cosmetics. This branding allowed them to be more discreet around their partners and also made them feel empowered and attractive, making taking HIV drugs a lot easier and desirable.

One of the hackathon groups experienced the power of an emotional response that hampered their policy ideas when they suggested an automated solution to gathering performance data in a health center. Speaking to health professionals, they found that they did not want to spend precious treatment time reporting data. They therefore suggested having ‘robots’ in each room that could monitor conversations, track the amount of time spent with each patient, and collect other relevant data about each health visit.

The team quickly modeled their solution with cardboard and pipe cleaners, and invited others to give feedback. While many agreed with automating the data collection process, a physical ‘robot’ made people feel slightly uncomfortable. What if something more subtle was used, like Alexa? It was clear from the participants’ emotional reactions that an alternative solution was needed to combat their visceral concern of a data-collecting entity that potentially violated their privacy.

Scrappy Prototypes offer powerful ways to learn fast and fail quickly.

Though the robot was ditched, having a model of it brought emotions to the surface. Perhaps without this prototype (which the participants built in no more than 30 minutes), participants would not have had this reaction and a version of a pilot may have been less critiqued.

This act of quick prototyping often provides an inexpensive method to learn fast and fail quickly. It goes a long way in illustrating ideas, aligning visions, and spurring key questions that may otherwise not be realised.

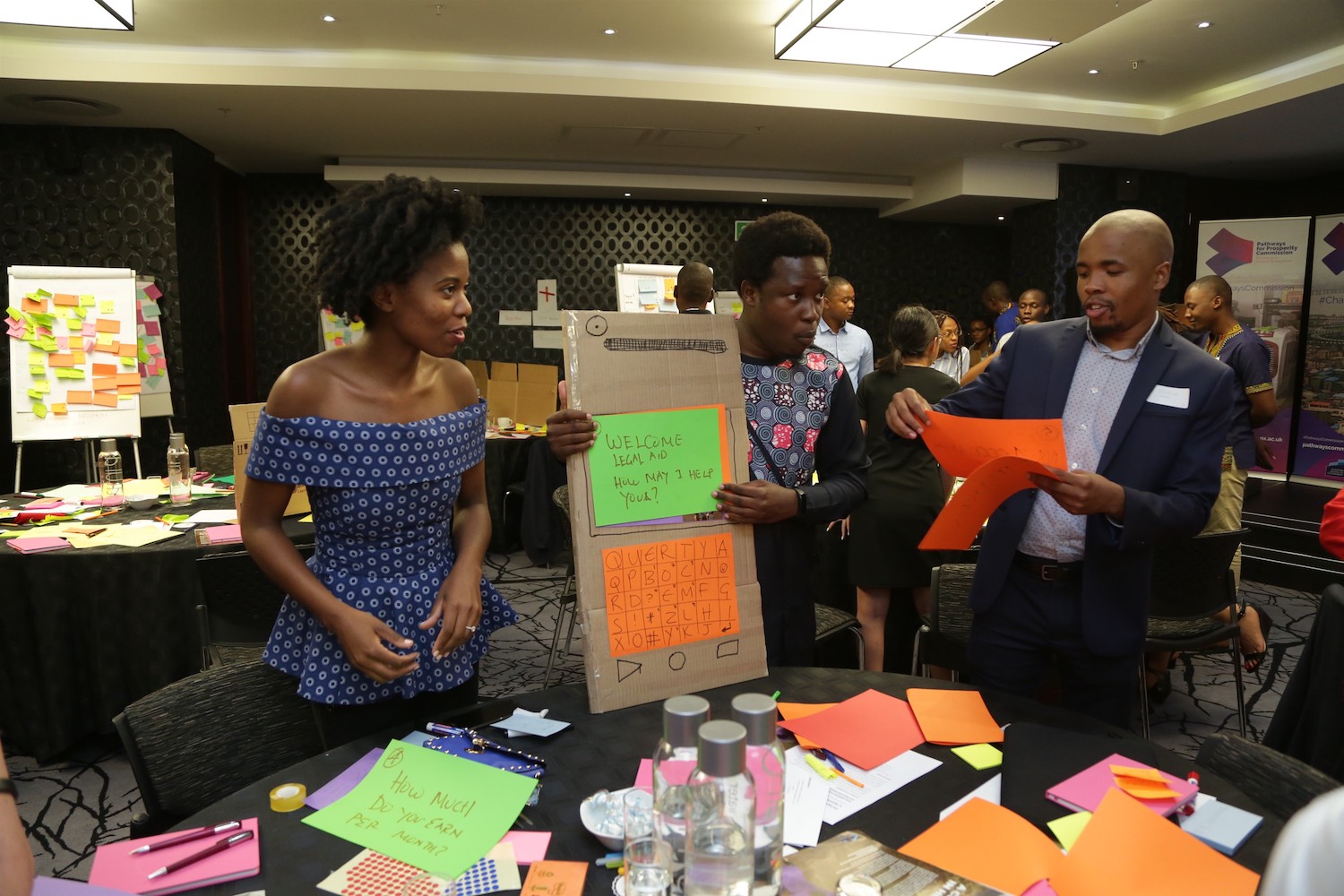

Digital solutions can benefit from rapid prototyping and iteration as well. For instance, one team was tackling the issue of providing legal aid. They settled on an SMS application system to help individuals living far away from the capital apply for legal aid. They started with the question that they were the most unsure of — what might the ‘conversation’ between the SMS app and the farmer look like?

The team wrote questions and responses on paper, and had someone role-play the mobile phone asking the question. The quick and easy (and free!) prototype allowed the team to ask further questions that were raised through this process — if it was an SMS system, how can the legal aid office trust self-reported data around income? Even within a snappy 30 minute exercise, a quick, non-digital prototype for a digital solution pushed what was simply an idea much further.

Technology works best when in sync with human structures.

Maria Ramos, a Pathways commissioner, notes that even though technology was a powerful tool, it is merely that: a tool. We should not expect technology to solve all of our policy problems, because many of these problems are human problems. At its worst, technology ends up amplifying many existing human problems. Think of AI that encodes human biases around race and gender. More often than not, they fail to consider existing human structures and needs, and therefore fail to produce any truly effective change. (Think One-Laptop-Per-Child.)

On the flip side, technology can also be in sync with human dynamics, in useful ways. In thinking about how to provide legal aid to those living in the most remote parts of Namibia, one of the hackathon teams built their solution on top of the ubiquitous spaza shops that exist across the country. Instead of a solution that required all individuals to be literate, they suggested using spaza shops as regional hubs where individuals could go to apply for aid, with the help of trained professionals that would travel to the spaza shops from time to time. This solution was sensitive to the actual needs of the beneficiaries of legal aid, as well as the social importance of spaza shops as the proverbial watering hole in the neighborhood.

While this was simply a hypothetical example of how technology can be effective when built on positive human structures, the real world provides many more such examples. An example is Go-Jek, a $5-billion ride-hailing and logistics company based in Indonesia. It took a hyperlocal approach to its model, understanding the local dynamics really well. Firstly, it used motorbike taxis, which are very common in Indonesia, as its main mode of transport. Secondly, it allowed users to pay in cash, a must-have for a country where many were unbanked. While technology is core in achieving operational efficiency, Go-Jek’s sensitivity to the human structures and dynamics on the ground were arguably key to its success.

Therefore, perhaps instead of asking the question, ‘how can we use technology to drive innovation?’ it might be wise to continue with the same policy questions, while keeping technology at the back of your mind.

Where do we go from here?

The above takeaways are mindset changes that will take time to develop for civil servants and people working in the social sectors. Running policy hackathons can help demonstrate these different approaches, but the real work is only beginning. Needless to say, a human-centred design approach toward policy is only one of many tools in creating and delivering effective public services. The biggest success of the day was that some of the participants have already planned or carried out hackathons in their home countries, or started introducing its methodologies in their departments - advocating for human solutions, not just technological ones.